Our guard force was a paramilitary organization that accomplished tasks in a standardized manner out of habit. We needed to send multiple teams to multiple places, which required proper planning to solidify the mission parameters that drove the rest of the planning. I pondered how to organize trips to various destinations without access to maps or up-to-date information when my XO Andy said, "Don't worry about it." I asked him for an explanation, and he said, “We’ll do this the Afghan way, which means you just get in the trucks and go. Inshallah, the roads will be clear, the weather fair, and the Taliban absent.” He had a point; we couldn’t get maps or intelligence products like we had when we were in the military. We could not anticipate what would happen the next day, so being alert was most important. That’s why I’ve always believed the best preparation for battle is a solid night’s sleep.

We rented a fleet of old, beat-up SUVs and sent the boys out to the four winds, expecting them to return at most seventy-two hours later. There were places we didn’t go, such as Nuristan province, a remote and treacherous region that most Afghans avoided. We avoided Farah province because it was full of belligerent armed miscreants, and Badakhshan province was so remote that nobody ventured up there. Elsewhere, internationals had no problem traveling the roads of Afghanistan and were treated with boundless hospitality when they arrived in remote areas.

I tagged along with the XO, heading to Jalalabad, just 150 kilometers east of Kabul. We stopped at the Nangarhar Province Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) base, where I heard there were Marines. I ended up running into an old friend, Andy McManus, who was the battalion commander of the 2nd Battalion 3rd Marines (2/3 in Marine speak). I asked him if he could help me out with AK ammo or medical supplies, and he looked at me like I was crazy. He had never heard of a Marine giving away serviceable ammo or medical equipment to anyone in the history of our Corps, adding he wasn’t going to be the first to break such a noble tradition.

Andy then looked at me curiously and asked why the embassy was begging for band-aids when the State Department had unlimited money to spend on security. I explained our multiple specified and implied tasks for which there was no corresponding funding. I then told him the RSO was pissed about losing his Marines before they had a properly trained guard force, which added a layer of friction to our efforts. I explained the limitations inherent in working for a British PMC, including the responsibility of executing poorly planned operations without the requisite authority to access additional project funding. Andy observed that working for a PMC sounded like being in the Marines, and the pay was better.

I asked what he was up to, and he told me he was working on an operation targeting a Taliban cell that had been planting IEDs and harassing Afghan security forces in Kunar province. He said they were currently in the mountains, and he had a good idea where, but he needed helicopters to execute the mission. He had no Marine air support in-country, so he had to borrow helicopters from the Special Forces Command in Bagram. They agreed to provide rotary wing support, but only if he used one of their SEAL Teams for the reconnaissance piece. He wanted to use his battalion’s Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) platoon, where the Marine Corps puts its school-trained scout snipers. Our conversation went something like this:

Me: “SEALs, huh? That sucks.”

Andy: “Yeah, I have no choice. I’m sure they’ll do fine, but I’d just rather have my guys doing it. My STA platoon kicks ass”.

Me: “Don’t blame you. Who wants strangers for the recon piece?”.

Andy: “We're going after some small-time punks, no more than a dozen, probably less, but they’ve been coming and going across the border, and we’ve got a good idea where they are. I’ve got enough time to lay the wood to them before I return to the States.”

We then talked about old friends before I took my leave. I remembered our conversation when the Lone Survivor incident happened later that year. A writer named Ed Darack was with Andy’s battalion, and he wrote a book titled Victory Point about the operations of Red Wings and Whalers. Victory Point explained the real story of that unfortunate incident, so if you’re a fan of the Lone Survivor book and movie, you won’t enjoy reading it. The book also validates Andy’s assessment of his sniper platoon. They would have their chance to shine in the coming weeks after the SEALs were lost, and they did not disappoint.

On that trip to Jalalabad, I first saw the Taj guesthouse. It had three large buildings, a detached tiki bar, and an in-ground, custom-built swimming pool that the resident UN road-building crew had installed for themselves. Like all Afghan compounds, it was surrounded by a solid, tall fence topped with barbed wire reinforced with a 30-foot bamboo screen around the pool deck. The road builders were Australian and New Zealanders, who were delightful company. They were working for the UN, which allowed them unlimited access to piss (beer). My XO decided to stay the night, but feeling the obligations of commercial command, I returned to Kabul with a dozen rifles and several thousand rounds of ammunition.

When I first drove to Jalalabad, it was a four-hour trip over a destroyed, shell-pocked roadbed. Within a year, a Chinese company paved the road between Kabul and Jalalabad. During the road construction, the Taliban or local criminals (it was often hard to tell the difference) tried kidnapping Chinese engineers for ransom. The Chinese never even acknowledged the ransom demands; it was cheaper for them to send more engineers, which is precisely what they did. In the years that followed, Afghans would joke, “All the dogs are gone; the Taliban must have let another one of them go,” as former Chinese hostages, released by their kidnappers, would show up in remote villages asking for food and a ride to the Chinese embassy in Kabul.

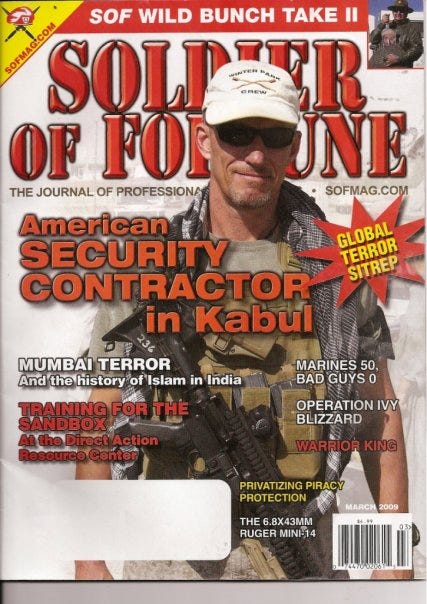

The drive between Kabul and Jalalabad within a year could be done in just over an hour if the road were clear. Within three years, there would be National Directorate of Security (NDS – Afghan Secret Police) checkpoints in the Kabul gorge where there was no cell phone reception. The NDS of Kabul liked to target foreigners; I wrote a blog post about losing two sets of body armor to one of these checkpoints in my Free Range International blog (more about that later), which was picked up by Soldier of Fortune magazine. My picture was on the cover (March 2009), resulting in some notoriety when I was recognized on the ISAF FOBs we frequented.

While we built infrastructure and fought to maintain security, the government in Kabul used that time and space to expand corruption. As more Afghans outside of Kabul experienced predatory shakedowns in dealings with the central government, they became increasingly hostile and uncooperative towards state agents. The worst aspect of this corruption involved land deed adjudication, which was so dysfunctional that by 2008, even Kabul officials took their legitimate land title claims to Taliban courts for adjudication[1]. Our military and State Department knew this ground truth, but could never acknowledge it.

On Saint Patrick’s Day 2005, we held the “assumption of contract” meeting, which brought together the senior management of the JV along with regional managers from my company, who were based in Dubai. Our relationship with the RSO had not improved, but our patron saint (Bruce the Patient) from the JV ran top cover for us. He stopped by the RSO shop daily to update them on our training and to field any complaints. We sorted Bruce out with a good house near the embassy in Kabul's Wazir Akbar Khan section. I also took him to Bagram Airfield to obtain a Common Access Card (CAC), which is vital for free-ranging around combat zones like Iraq or Afghanistan.

We discovered in the State Department contract that I, as the program manager, had the authority to sign CAC card applications. I already squared away the guard supervisors with cards and explained to Bruce the importance of having the CAC. They gave you access to ISAF bases where you could eat at the dining facilities (DFACs), fill up your vehicle in the base fuel pit, establish a military post office box, and access the American army exchanges and gyms. The Kabul restaurants were expensive, and eating food prepared by local cooks was risky, so Bruce caught on quickly to the benefits of living the Free Range lifestyle.

The problem of contractors freeloading on American Army bases lasted only briefly. In 2006, Bruce and I, enjoying our daily breakfast at Camp Eggers together, witnessed the Army cracking down on CAC card-holding freeloaders. The base Sergeant Major stopped two of our guard supervisors to berate them for eating in his DFAC, despite not being authorized to be on the base. He paused when Bruce and I walked up and said, “You boys need to be authorized to be here like Mr. Lynch and Mr. Maler.” The two looked at me in shock, and I winked at them as we hurried past. The advantage of using the same DFAC almost daily was that when the troops rotated out, those rotating in assumed we belonged because we were already there when they arrived.

After getting Bruce squared away with decent quarters, we brought him up to speed on what we were doing and the associated administrative burden of documenting training and writing detailed Standing Operating Procedures (SOPs) for the guard force. The current SOP was written for Marine Corps rifle companies with fewer men but more firepower than we had, and they were living on the embassy grounds, so their SOP was worthless. Developing detailed tactical Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) was a standard part of any battle drill in the military, and we knew how to write effective ones. I learned through Bruce that the RSO worked through the seven stages of grief over the loss of the Marines, so his attention had shifted to bleeding us dry with the non-compliance fines listed in the contract. The JV was already going to take a hit for the TCN guards arriving a week late, but I was determined that they would not lose a penny over matters we could control.

I had been an instructor at Front Sight Firearms Training Institute in Las Vegas for years before getting into contracting. Over the years, I attended the FBI firearms instructor course and a half dozen three-gun instructor development courses. I was credentialed as a pepper spray, baton, and handcuffing instructor, as did the project training team and several other guards. This impressive list of qualifications was relevant only because I had detailed class outlines and training schedules for every training course. With detailed instructor outlines for our rifle, pistol, shotgun, pepper spray, baton, handcuffing, and vehicle searches in hand, all we needed to create were embassy-specific gate procedures and standing orders for our unarmored quick reaction force (QRF). We war-gamed all those procedures, tuned them up for specific attack scenarios, and ended up with a kick-ass guard force SOP.

All the guard supervisors passed the weapons qualifications on the first try. We only had to qualify with the AK-47 rifle and Glock pistol, which wasn’t that hard if you had relevant weapons training and were accustomed to handling guns. AK-47 rifle qualifications were easy as long as you had front and rear sight adjustment tools to zero the rifles, which we did; the M4 qualification tables were much more challenging.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tim’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.