Betrayal of Command

The book that launched an epic rant Part 1

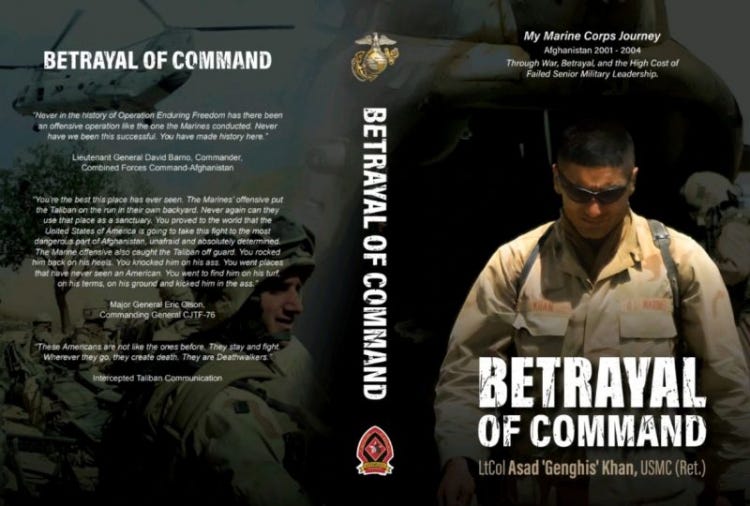

Last month, my friend Asad Khan released his autobiography, Betrayal of Command: My Marine Corps Journey. The book focuses primarily on his 2004 command of the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines (1/6) in Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan. Asad Khan is the toughest Marine Corps infantry officer I know, and that’s saying something. Marine Corps infantry officers, before training standards were lowered to shoehorn women into the front lines, had earned a legendary reputation for toughness. I knew him when I was on active duty and bumped into him several times in Afghanistan after we both retired. I greatly respected Asad when we served together on active duty. After reading his book, my respect has grown.

If you were mystified by the gross incompetence of the Kabul withdrawal fiasco or surprised by the collapse in prestige among America’s senior flag officers, this book explains both. It is also the best combat leadership book written since Colonel Hackworth’s About Face. In fact, it’s better than Hackworth’s outstanding memoir because it reads like James Webb’s Fields of Fire or Karl Marlantes’s Matterhorn, two of the best works of fiction about Vietnam.

I wrote about Asad last year after two FBI agents visited him to investigate the “anti-American” views he expressed on his Sentinel YouTube channel. That incident made me jealous because I’ve been writing pieces critical of feckless politicians, the expert managerial class, the medical establishment, and the military for years. Yet, I’ve never received a visit from the FBI.

Many of the books by the post 9/11 military veterans come off as self-promotion: it’s hard to write about yourself without sounding egotistic. A mutual friend of ours told me that Asad’s greatest strength is that he’s unrelenting. He then added that his greatest weakness is that he’s unrelenting. That unrelenting nature comes through loud and clear in his autobiography, which is how he avoids the self-promotion trap.

But that same unrelenting character made Asad a difficult subordinate. That’s not unusual. I could be a difficult subordinate, and so could every one of my close Marine Corps friends. It’s easy to work for strong, decisive, well-rounded leaders you admire. You never want to disappoint the men you wish to emulate. But when you get a leader who is not physically hard, well-read, or tactically proficient, life can be difficult.

When Asad and I were company-grade officers, the Marine Corps was full of battle-hardened Vietnam veterans commanding its infantry battalions and regiments. They could run your ass into the dirt and then do 20 dead hang pull-ups despite being pack-a-day cigarette smokers. Working for men like that is a pleasure because you know exactly what’s expected of you. If you took care of your Marines, were technically and tactically proficient, and remained in top physical condition, you were golden.

Asad Khan had been a golden boy throughout his Marine Corps career until fate dealt him a bad hand: the Battalion he was assigned to command, 1/6, was up for a MEU rotation, and the Commander of the 22nd MEU was the exact opposite of Asad. Kennith F. McKenzie Jr. was an intelligent man who thrived on staff work at higher headquarters. He was not physically fit, lacked an affinity for enlisted Marines, and was overly enamored with the perks and privileges afforded to senior officers.

It is not uncommon to encounter senior Marines who are ineffective leaders. They are easy to spot because effective senior commanders, by definition, favor Marines at the tip of the spear and are hard on their staffs. Ineffective commanders are loved by their staff officers because they hide behind them and do not force their staffs to support the Marines at the point of contact. This pattern holds across infantry, recruiting, and training commands.

There is a subset of ineffective commanders who are dangerous because they are above average on the three personality traits of the dark triad. Harvard professor Dr. Arthur Brooks contends that 7% of the population exhibits the dark triad of personality traits, which are:

Narcissism — it’s all about me

Machiavellianism — I’m willing to do what it takes, including hurting you to get my way.

Psychopathy — I’m going to hurt you and feel no remorse.

Based on Khan’s description of Kennith F. McKenzie Jr., he was one of the 7%. Working on McKenzie’s staff was not risky because he treated them like trusted toadies whom he entertained in the flag mess. Working for him as a subordinate commander placed one in grave danger, especially if that subordinate was so talented that he attracted attention and accolades from McKenzie’s senior commander or, heaven forbid, the national media.

Officers who knew McKenzie well throughout his career told me he was an unpopular, uninspiring rifle company commander, but an effective, proficient infantry Battalion commander. He was known as a bright guy who could write well and was an efficient staff officer. As a general officer, he held a series of staff positions until he was promoted to Lieutenant General. At that point, he was sent to CENTCOM to head the United States Marine Forces Central Command. That is another staff billet because it doesn’t own any Marines but manages Marine units assigned to CENTCOM. Why he was selected as the commander of CENTCOM is a mystery buried inside the Joint Command Sausage Factory.

Asad Khan passed the only test that matters among his peers: Would I want my son to serve in his Battalion? When my good friend Jeff Kenny’s son was graduating from boot camp in 2003 and heading to Camp Lejeune for his first assignment, Jeff, who had the connections to get him into any Battalion at Lejeune, made sure he went to 1/6. He knew Asad well and didn’t want his son to go to war with anyone other than Khan.

When the 22nd arrived in Afghanistan, the MEU was assigned to CJTF 76, commanded by Army Major General Greg Olson, who approved the MEU’s proposal to ‘secure’ Uruzgan Province and register voters for the upcoming presidential elections. Uruzgan Province, like Helmand Province, would become a Taliban-dominated battleground. ISAF units would suffer significant casualties in both. But in 2004, it was, like Helmand Province, relatively secure. The crafty warlord Sher Mohammad Akhundzada, with his large militia, had Helmand well in hand. Uruzgan had Jan Mohammad Khan, another effective warlord with a large militia, and together they had driven the Taliban out of most of the province.

The 22nd MEU presented a five-phase plan to occupy Uruzgan Province, supported by hundreds of PowerPoint slides but with no written orders or detailed planning. The last two phases (decisive operations and transition & retrograde) were placeholders with no plans. The plan designated the seizure of objectives in a rigid, methodical progression on a strict timeline. To make this plan work, McKenize stripped 40% of the maneuver units from Battalion Landing Team (BLT) 1/6 and placed them under his direct control.

McKenzie made one reasonable decision about his upcoming fight: to give BLT 1/6 a broad area of operations, allowing Lt. Col. Khan to set his own objectives. Once the 22nd MEU was established at its new base in Tarinkot (the provincial capital), Asad rolled Provincial Governor Jan Mohammad’s militia into his Task Force (TF), named it TF Genghis, and then went on a rampage through the mountains of Uruzgan, Kandahar, and Zabul provinces.

It did not take long for word to spread to the hinterlands that the Americans had sent a Pashtun commander leading an army of infidels who were separating the Taliban from the population and killing them. It is important to note that the rural Afghans living in the remote mountains and valleys had no idea why the Americans had invaded their country. They did not know about 9/11 and had never heard of Osama bin Laden or al-Qaeda. They weren’t fond of the Taliban because of their prohibition on smoking tobacco, but their lives had changed little since the Soviets had been expelled.

Afghans from the surrounding area flocked to meet Asad, seeking his help with disputes, medical care, and civil matters, such as the management of drinking wells and irrigation systems. Asad became well known among rural Afghans, and years later, when I was in the South, locals would ask whether I knew Commander Khan. When I replied that we had been friends for the past 20 years, I gained instant credibility and respect.

Word of TF Genghis quickly reached the theater-level signals intelligence apparatus, which monitored Taliban communications referring to BLT 1/6 as the death walkers. They were so well-known that Fox News sent Geraldo Rivera to interview Asad. The seven-minute segment focused exclusively on Asad and his Marines and made no mention of the 22nd MEU or Frank McKenzie.

During the interview, Geraldo mentioned the one Marine BLT 1/6 lost to the Taliban. He was a 6’7”, 250-pound Corporal, Ron Payne, in the Light Armored Reconnaissance (LAR) platoon. Khan became visibly emotional at the mention of his name, tearing up as he described how painful Cpl. Payne’s loss was to him. He caught himself, his face hardening, and added, “We’re going to kill some more Taliban, I’ll tell you that. We’re going to find them, fix them, and finish them.” That interview is at the end of the Sentinel video embedded below.

The LAR platoon had been detached from BLT 1/6 and was working directly for the 22ndMEU, which had it stationed at a checkpoint on the southern end of Daylanor Pass, near the hamlet of Tarwa—sixty kilometers from the FOB. An LAR platoon consists of four vehicles, each with a three-man crew and four scouts. It is a small unit, and although the LAVs are armed with 25mm Bushmaster autocannons, LAR Marines are tethered to their vehicles. Leaving them that far out in complex mountainous terrain was reckless. Asad had warned against leaving his LAR platoon isolated and exposed, and he was furious about losing one of his Marines in such a careless manner. After this ambush, the LAR Marines were replaced by the governor’s militia.

Asad, like many Marine infantry battalion commanders, repeatedly said he intended to bring all his Marines home with him. I’ve never thought that a realistic expectation, and for most deploying infantry units, it wasn’t. But in 2004, at the dawn of our Afghan adventure, Asad almost pulled it off. The Taliban of that era didn’t realize that massing fighters to attack Marines was suicidal. They hadn’t learned about the Marine infantry’s annoying tendency to run into their fire so they could throw grenades at them. Back in 2004, the Marines weren’t constrained by ridiculous rules of engagement dreamed up by four-star generals trying to avoid censure from fickle politicians or clueless Presidents. They were free to do what they did best, close with and destroy the enemy.

Tim. I am humbled by your words and don't take them lightly. I appreciate your support and our brotherhood. Semper Fi and a Healthy 2026. 🤗🫡🇺🇸

Hey, Tim.... Thanks for continuing to educate me and other somewhat familiar civilians out there: RESPECT!